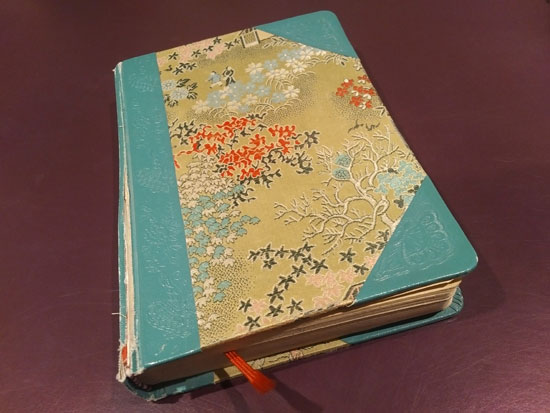

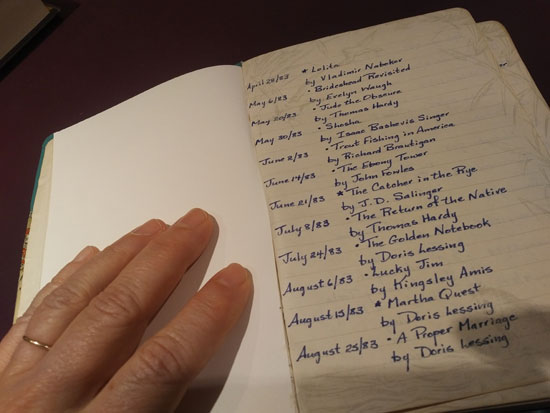

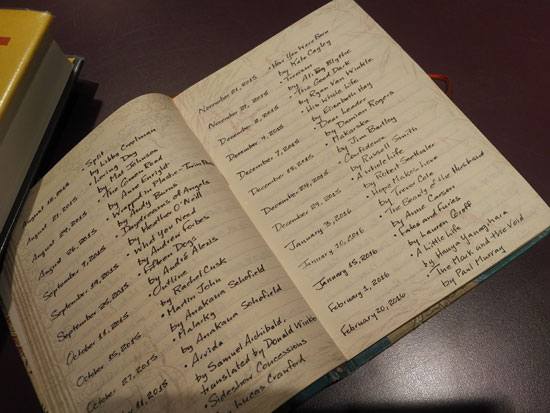

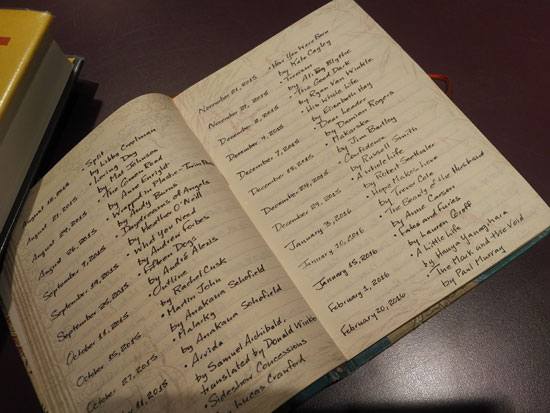

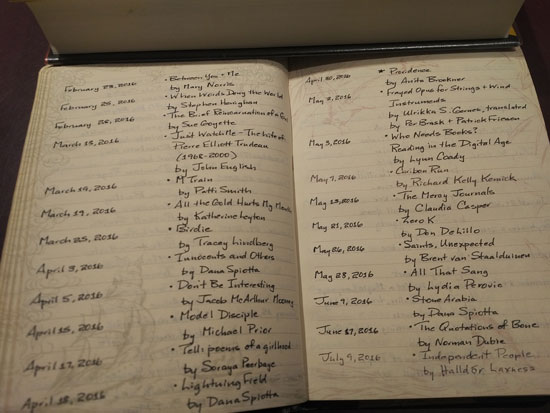

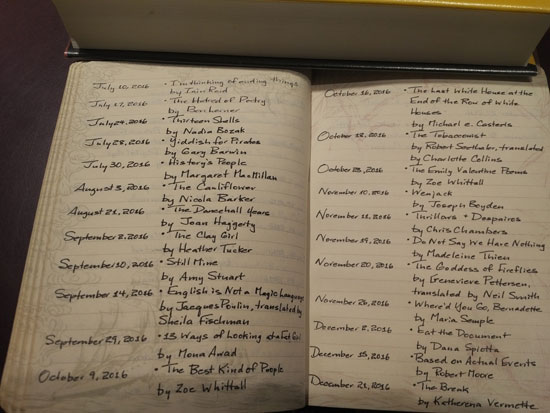

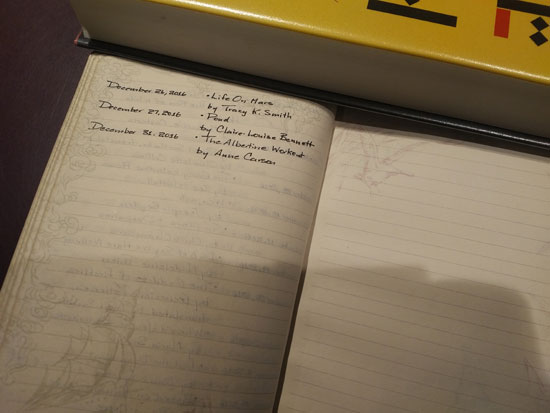

When I graduated from university, I started to keep track of my books read in this wee diary that was a gift from my roommate.

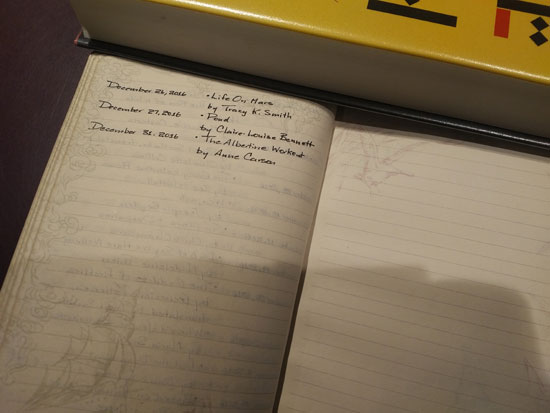

I started the books diary in 1983. It’s coming apart at the seams a bit. Over the years, I’ve backed up my list in databases, spreadsheets, Goodreads and other book apps du jour … but I’ve always updated this little diary as part of my reading routine. Yes, this book and this part of my reading ritual is getting on 34 years …

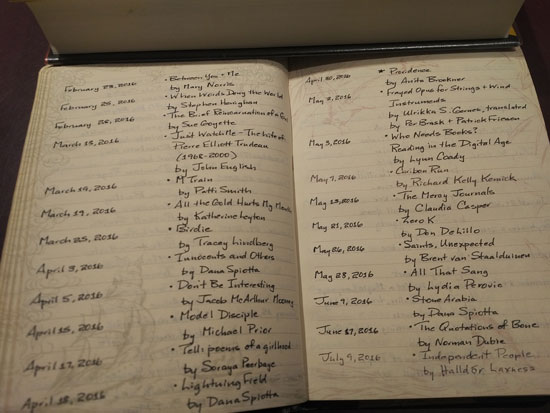

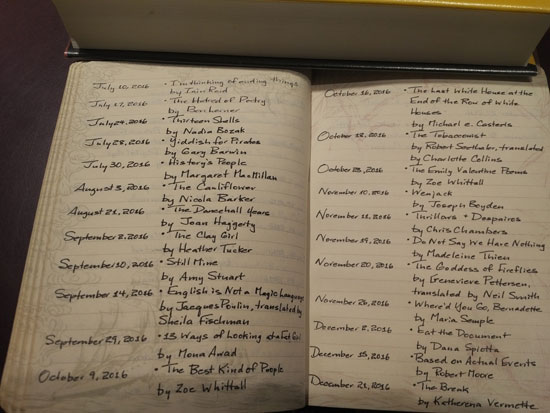

Here are the books I read in 2016 – once again, diligently recorded in my book diary, along with a backup spreadsheet and Goodreads – with links to reviews where I have them. By the way, this is an exhaustive, “all of” list, not a “best of” list.

I welcomed some wonderful and insightful guest reviewers and correspondents to this blog in 2016. I’m so grateful for the time and thought they spent on their pieces, from which I learned a lot and hope you did, too. Let’s revisit them again:

Here are the books I read, reread and read aloud in 2016. Wherever I go, I try to carry a book with me, so for each book, I’m also going to try to recall where I was when I was reading it.

-

Hope Makes Love

by Trevor Cole

I vividly recall reading this book at the cottage during the wintry first days of the new year.

-

The Beauty of the Husband

by Anne Carson

I was reading this amazing book while waiting for a friend who was arriving by GO Train at Toronto’s Union Station. We were meeting another friend to go to a poetry reading – how perfect is that?

-

Fates and Furies

by Lauren Groff

I distinctly recall reading this engrossing book snuggled in bed.

-

A Little Life

by Hanya Yanagihara

I went through a protracted period of insomnia last winter and if, after trying to relax and consciously breathe myself back to sleep, I was still wide-eyed in the dark, I would turn on my little book-light and read. This book actually didn’t help get me back to sleep – quite the contrary – but it was stunningly memorable company during those sleepless hours. What an unforgettable wallop of a reading experience.

-

The Mark and the Void

by Paul Murray

I read this two-volume paperback (a very interesting packaging of the story) mostly at our dining room table. It was February, when this household observes a month of abstinence from alcohol, so the accompanying beverages were likely tea and coffee.

-

Between You & Me

by Mary Norris

I took this entertaining book with me on more than a few subway rides.

-

When Words Deny the World

by Stephen Henighan

This book kept me company on streetcar rides to physiotherapy appointments.

-

The Brief Reincarnation of a Girl

by Sue Goyette

I read this gorgeous book (also a gorgeous book object) at home.

-

Just Watch Me – The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1968-2000)

by John English

(read aloud)

A lot of our reading aloud takes place in the kitchen, with my talented husband cooking and me singing for my supper. We actually read a lot of this book during the interminable 2015 Canadian federal election and it was a great reminder that there were dedicated, thoughtful and honorable politicians of all political stripes as recently as just a generation or two ago.

-

M Train

by Patti Smith

I read this sweet, luminous book at home.

-

All the Gold Hurts My Mouth

by Katherine Leyton

This poetry collection was company on several subway rides.

-

Birdie

by Tracey Lindberg

This book was warm and fascinating company on streetcar rides to physiotherapy appointments.

-

Innocents and Others

by Dana Spiotta

Among his many talents, my husband is a great seeker and finder of first editions of books. When I fell in love with author Dana Spiotta on the basis of this intriguing New York Times Magazine interview, he made it his mission to find all of her novels for me. And then I read them all this year. To a book, they were amazing. I already can’t wait for what she’ll do next.

-

Don’t Be Interesting

by Jacob McArthur Mooney

I read this collection (which had me at the John Darnielle references) at home and on public transit.

-

Model Disciple

by Michael Prior

This collection was fine company during the continued streetcar rides to physio appointments.

-

Tell: poems for a girlhood

by Soraya Peerbaye

You know what? I was so wrapped up in the entrancing, often horrifying but also heartwrenchingly beautiful world of this collection that I in fact don’t recall a specific place or moment when I was reading it. What does that say?

-

Lightning Field

by Dana Spiotta

I read this book at home, probably mostly at my desk and the dining room table.

-

Providence

by Anita Brookner

(reread)

I read this tiny, battered, much loved paperback on the subway, where a fellow passenger remarked that it was her favourite Brookner.

-

Frayed Opus for Strings & Wind Instruments

by Ulrikka S. Gernes, translated by Per Brask and Patrick Friesen

This poetry collection accompanied me on more than one road trip.

-

Who Needs Books? Reading in the Digital Age

by Lynn Coady

I pretty much read this in one sitting … with lunch.

-

Caribou Run

by Richard Kelly Kemick

I read this very fine collection at home, on public transit and I recall packing it along to the cottage, too.

-

The Mercy Journals

by Claudia Casper

I remember reading this haunting novel late at night at the cottage.

-

Zero K

by Don DeLillo

I vividly recall reading most of this book in an incredible, absorbing whoosh while driving home from the cottage. (No, I wasn’t driving.)

-

Saints, Unexpected

by Brent van Staalduinen

I remember reading this fine and amiable book while relaxing on the back porch.

-

All That Sang

by Lydia Perovic

I pretty much had this captivating book read in a couple of subway rides and a sit on the front porch.

-

Stone Arabia

by Dana Spiotta

I remember being absorbed in this book while sitting on the cottage dock with a refreshing beverage or two.

-

The Quotations of Bone

by Norman Dubie

Subway reading, I do believe …

-

Independent People

by Halldor Laxness

This one took a while to read – which was fine, as it was a read to savour and get immersed in – so I had it with me everywhere. It’s another book that a fellow subway rider remarked on, most enthusiastically.

-

I’m thinking of ending things

by Iain Reid

I had the good sense to only read this book during daylight hours.

-

The Hatred of Poetry

by Ben Lerner

Some subway rides went quickly with this wise book for company.

-

Thirteen Shells

by Nadia Bozak

I was reading and enjoying this book during a weekend visit with friends at our cottage.

-

Yiddish for Pirates

by Gary Barwin

This book was thoroughly delightful company during a week’s vacation at the cottage.

-

History’s People

by Margaret MacMillan

(read aloud)

We read this book aloud – and learned a lot about greater and lesser known historical figures – during cozy reading sessions at home and at the cottage.

-

The Cauliflower

by Nicola Barker

Not my favourite Barker, although Barker remains one of my favourite writers … I read this book while on my own for a working week at the cottage.

-

The Dancehall Years

by Joan Haggerty

Remembering this book reminds me of our shade-dappled dock at the cottage.

-

The Clay Girl

by Heather Tucker

I will remember The Clay Girl and the next book on this list, Still Mine, side by side and as my constant companions everywhere (home, out and about, cottage) for two or three weeks. I had the honour in 2016 of moderating a couple of special book club events for the Toronto Word on the Street Festival. Selected contest winners qualified for small, private book club meetings with authors Heather Tucker and Amy Stuart, and it was my job to introduce them to their book fans and keep the conversations going with pertinent questions about their respective books. I prepared exhaustively with questions and observations … but then didn’t need a lot of those preps because those book fans showed up excited, motivated and brimming with their own wide-ranging queries and reflections. It was really rewarding to see such warm and dynamic meetings of readers and writers – truly wonderful!

-

Still Mine

Amy Stuart

See my comments about The Clay Girl … I also recall enjoying Still Mine on a coffee shop patio on a sunny Saturday morning while waiting for my husband.

-

English is Not a Magic Language

by Jacques Poulin, translated by Sheila Fischman

This charming novella was good subway company.

-

13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl

by Mona Awad

I read this book at home and out and about.

-

The Best Kind of People

by Zoe Whittall

I read this book at home and out and about.

-

The Last White House at the End of the Row of White Houses

by Michael e. Casteels

I recall being wrapped up in this enchanting little collection while waiting for my husband to join me for dinner out.

-

The Tobacconist

by Robert Seethaler, translated by Charlotte Collins

I read this fascinating and rather prophetic book at my desk in my home office, as I prepared the readers’ guide / book club questions for this book, offered by House of Anansi Press.

-

The Emily Valentine Poems

by Zoe Whittall

A squirrel jumped up next to me on the park bench I was sitting on as I read this while waiting for a friend in a parkette outside her office in downtown Toronto.

-

Wenjack

by Joseph Boyden

I read this small, moving book in one sitting at home.

-

Thrillows & Despairos

by Chris Chambers

I discovered this collection when I heard Chris Chambers read from it at the 2016 International Festival of Authors, and I ran to the book table and purchased it right after the reading. Immersive indeed!

-

Do Not Say We Have Nothing

by Madeleine Thien

This beautiful book was constant, contemplative company at home throughout the fall.

-

The Goddess of Fireflies

by Genevieve Pettersen, translated by Neil Smith

I remember standing on subway platforms with this book in my hand.

-

Where’d You Go, Bernadette

by Maria Semple

I remember carrying and reading this sweet book on transit and waiting for friends at restaurants and before musical events in late November.

-

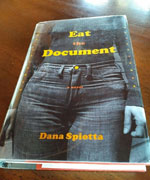

Eat the Document

by Dana Spiotta

I read this intriguing book, the final in my year-long Dana Spiotta-fest, at home.

-

Based on Actual Events

by Robert Moore

Devoured in just a few subway rides, I believe …

-

The Break

by Katherena Vermette

I had this absorbing book with me at home, out and about and even on a wintry trip to the cottage.

-

Life On Mars

by Tracy K. Smith

I stayed up late reading this gift on Christmas night.

-

Pond

by Claire-Louise Bennett

I treasure this quirky read, a spontaneous gift from a lovely colleague.

-

The Albertine Workout

by Anne Carson

Another Christmas gift, I read this poetry pamphlet pretty much in one gulp while sitting at my home office desk.

In 2016, I read a total of 54 works: 32 works of fiction (novels and short story collections), 15 poetry collections and 7 works of non-fiction. I re-read one book, read 4 works in translation, and read 35 works by Canadian authors. My husband and I read two books aloud to each other this year and have a third in progress as we greet the new year.

Looking back fondly on my 2016 reading, looking forward eagerly and with anticipation to my 2017 reading, I’ll simply conclude (as I’ve done in previous years) …

I love the discussion this post has sparked, both here and on social media, including some debate about whether or not such list-keeping is usual or kind of nutty/anal-retentive. Obviously, keeping these lists every year is part of enjoying my reading. I’ve added a bit more to my scrutiny of what I’ve read every year, not so much with a view to altering the flow of what I decide to pick up and read every year as to just be aware if there was more or different directions in which I should explore. So, for example, I’ve looked in recent years at how much fiction vs non-fiction vs poetry I read, and how many works in translation, how much Canadian versus international literature, how many rereads, read-alouds, etc, etc, etc. Because the lists are easy to scan, I can quickly figure out the author gender mix every year … just to see how I’m doing, usually not to be corrective in my reading habits.

One thing I’ve decided to add to my record-keeping in 2017 is the publication year of each book read, to gauge how much current/hot-off-the-press vs back catalogue/older stuff I’m reading. I love that everyone who has joined this conversation loves their reading, loves to examine it to some extent and loves to share it. We all learn and benefit from that.

André Alexis’ novella A packs an incredible amount to enjoy and ponder in its infectious 74 pages.

André Alexis’ novella A packs an incredible amount to enjoy and ponder in its infectious 74 pages.