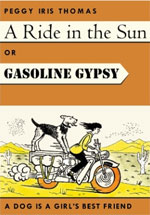

I’ve mentioned before that my husband Jason and I have combined our love of books with our love of dogs (Airedale terriers in particular) by building a library of books in which Airedales have starring or supporting roles, or at least appear in all their handsome splendour on book covers. Jason and I also, by the way, regularly enjoy sharing our books by reading aloud to each other. We combined all of these pleasures when we read together A Ride in the Sun, or Gasoline Gypsy, by Peggy Iris Thomas, earlier this year.

This book has many charms. The author recounts the myriad adventures she and her Airedale, Matelot, enjoyed as they embarked on a 14,000-mile motorcycle trek through Canada, the United States and Mexico from 1950 to 1952. As an unassuming paean to a considerably more innocent time, it’s a delight. At every hairpin turn along the way, Peggy miraculously finds a trucker who will pick up her woefully underpowered and overloaded motorcycle and transport it to the next garage. With only one or two comically villainous exceptions, those garages are staffed by resourceful mechanics willing to figure out the vagaries of her unusual model of bike and get her back on the road again – often no charge. At times fearless and self-sufficient, at times naively hapless, Peggy is always captivating, and Matelot is the epitome of canine patience and fidelity.

We relished all of these charms and they seemed to shine through most brilliantly when we were sharing the book together, reading it aloud, laughing, pausing to comment on Peggy’s misadventures, close calls and feisty spirit, and to stray into our own stories. When we paused to stumble just a bit over yet another repetition of Peggy’s stock phrases or stilted prose, the fact that we were reading it all aloud helped us to compensate, laugh it off and carry on. The few times we tried to read portions of the books to ourselves, the story fell calamitously flat, freighted under the words of someone more comfortable riding a motorcycle or training dogs than capturing any of it in sentences. And hence the glory of reading aloud to redeem great stories somewhat awkwardly told.

See also:

60th anniversary edition of A Ride in the Sun, or Gasoline Gypsy, by Peggy Iris Thomas

Benefits of reading aloud

(While there is much to be said about children reading aloud, adults reading aloud to children, and adults reading their own prose aloud to remedy problems in expression, it’s hard to find much about the joys of adults reading aloud to adults. Leave a comment on this post if you find anything, OK?)

- Reading Aloud

LSC 300 L Literature for Children

Department of Library Science and Instructional Technology

Southern Connecticut State University, New Haven CT - 7 Ways Reading Aloud Improves and Enriches Your Life

(Vox Daily / Voices.com) - The Advantages of Reading Aloud

(About.com / Grammar & Composition)