I’m delighted to introduce Bookgaga blog visitors to another splendid guest book reviewer. Barbara McVeigh is a dedicated and enthusiastic teacher-librarian working in Southwestern Ontario. She’s a writer and avid, omnivorous reader who combines her own interests, such as cycling, with particular emphasis in her reading and book curating on the area of sport literature. Barbara is active on Goodreads, and you’re guaranteed a lively discussion when you converse with her via Twitter – @barbaramcveigh.

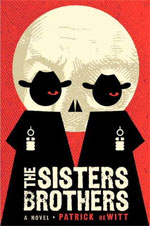

The Sisters Brothers: A Defense

I was reluctant to read The Sisters Brothers for a long time. It was getting mixed reviews and being nominated for so many damn awards. Not a good sign. However, I bought (and read) the book because I was attending the Stephen Leacock Medal presentation, which The Sisters Brothers had won.

The book has been criticized as not having a story, for having too much senseless violence, and for its weird, anachronistic language and characters. Because of all these reasons, I loved the book.

In terms of plot, The Sisters Brothers moves along in short chapters. Each chapter left me breathless and wondering where the characters were going to next. We do not expect what happens to happen. For example, after being treated for a tooth infection and then robbing the dentist of his novocaine, the narrator defies a witch’s curse in order to save a horse he doesn’t want from a grizzly bear. These short chapters allow the brothers to quickly move from place to place and interact with the best the Wild West has to offer.

The novel also delivers emotional sucker-punches and subverts the expectations of the Western genre. In a typical Western, you’d have two cowboys in white hats who come to save the day. Instead, we have the brothers Charlie and Eli Sisters whose job it is to mercilessly kill Hermann Kermit Warm, and dispose of anybody who gets in their way. When hatching a plot, Charlie says: “Morals come later. I asked if [the plan] would make sense” (DeWitt 222). As they head towards their mission and move from misadventure to misadventure, we cheer them on.

The strength of the subversion lies in the empathy the reader feels for Eli Sisters. I read this book out loud to a student and was immediately struck by the strength of the voice: gravelly, rolling and soaked with whiskey. Now Eli isn’t just your run-of-the-mill heartless killer. He’s looking for true love and personal improvement. He is also loyal to his bloodthirsty brother. Yet, Charlie (whom is often described as a psychopath in reviews) doesn’t always come across as the baddest of the bad, either. At one point Charlie tells Eli the story of how Eli got his freckles. The story demonstrates their brotherly bond, as well as revealing Charlie’s protective spirit.

Still, these aren’t men in white hats. When the brothers are in situations where they could behave as if they were good guys, they defy our expectations. On their way to California to find Warm, Eli and Charlie come across a 15-year-old boy alone in the wild. They give him food and listen to his life story. Apparently, everyone who meets this boy hits him on the head. In the usual Western script, the reader would expect that the two heroes would adopt the boy and care for him. But Charlie and Eli can’t: They’re assassins. They hit the boy on the head to disarm him and then abandon him (not once, but twice) on their journey.

The reality of scenes like this would be horrible if played straight. Patrick DeWitt at the Stephen Leacock presentations spoke about using comedy as a weapon. The humour deflects the bite of reality. This is the Wild West “where life ha[s] no value” (Fisher). The boy evokes every sense of pathos: no mother, a missing father, unrequited love, and a naive optimism that the brothers will take him under their wing. Their interaction is touching and funny, and then the boy disappears from the book. Like all the minor characters in the novel, whether it be the intermissions girl, the dirt coffee prospector, or the weeping man, these characters appear “for no real reason” (Edwards). In an interview, DeWitt says that these characters have no symbolic value; they are just “semi-humorous vaudevillian prop[s] wandering into someone else’s scene” (Edwards). What these characters do provide is the quirkiness and atmosphere for this great rollicking story.

The action quickly continues to California and comes to an unexpected conclusion. There’s a moment when the elastic seems to snap backwards and fortunes are reversed, much like Martin Amis’s Time’s Arrow.

Initially, I felt the ending wasn’t satisfactory. There’s a reversal of position for Eli and Charlie, but I wanted them to get some sort of reward. A few readers (and definitely some characters) might say that, in the end, Charlie and Eli got their “just desserts”. Still, I felt that since we’ve grown to like these two anti-heroes, something good should’ve happened to them. But then I found, on second thought, that something good does happen; it’s just not in terms of a monetary prize.

Comedy as a weapon not only deflects the harshness of reality. If the humour is sharp, it also reveals a message or truth. And what does the humour of The Sisters Brothers reveal? That despite “the difficulties of family [and] how crazy and crooked the stories of a bloodline can be” (DeWitt 11), it is only family you can trust. In a world that changes in the blink of an eye and where life has no value, it is only with family you can find safety and home.

So should you read The Sisters Brothers, especially since there’s a danger you may hate it rather than love it? Here’s the warning I like best: “If the characters and briskly paced events don’t appeal to [you] early, it is unlikely it will get better” (Trembley). If you can preview the book, do. I strongly recommend that you saddle up and go on a wild ride with Eli and Charlie Sisters.

Works Cited

DeWitt, Patrick. The Sisters Brothers. Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2011. Print.

Edwards, Art. “An Interview with The Sisters Brothers Author Patrick deWitt.” The Nervous Breakdown. 13 July 2011. Web. 13 June 2012.

Fisher, Austin. “Chapter II: A Fistful of Lire.” Dissertation. Sergio Leone and the Western Myth: Reading the Ritual. 50Webs.com. 2000-2001. Web. 15 June 2012.

Trembley, Dave. Comment on Goodreads. 25 January 2012. Web. 13 June 2012.