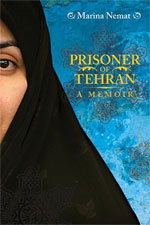

The Penguin paperback edition of Prisoner of Tehran offers a subtle but arresting feature that I hope is part of the original and any other editions of this fine book. You can see Persian emblems or motifs in spot varnish when you tip the book cover in the light. Curving over the book spine and extending to the back cover, you can feel their faint imprint as you’re holding the book – which you likely won’t do for long, because the book is a compellingly swift read. It’s a lovely, pervasive reminder of the book’s cultural underpinnings. The emblems also hauntingly resemble snowflakes – imagery that recurs to surprisingly powerful effect throughout this unforgettable story.

Author and protagonist Marina Nemat quickly ushers you into a riveting account of her terrifying experiences during the Iranian revolution of the early 1980s. Her voice has the flat affect of someone battered and shell shocked, but strikingly determined to survive. While that voice is at times so strangely modest and understated as to be almost unnerving, you are irresistibly drawn into her harrowing tale of being arrested at the age of sixteen for acts so tenuously seditious to the regime of Ayatollah Khomeini as to be ridiculous. It is that ridiculousness that makes the physical and mental tortures she endures that much more nightmarish and incomprehensible. The terms by which she negotiates – if it could be dignified to call it such – and the circumstances by which she navigates her eventual freedom, after over two years of prison life, are almost inconceivable and border on the surreal. Nemat’s prenaturally calm voice throughout it all helps you to stay with the twists and turns – sometimes heart pounding, sometimes heart wrenching, sometimes grindingly banal – that she and the other young women with which she is imprisoned face almost daily. Raised as a practicing Christian in a middle class, fairly secular and unashamedly Westernized family, Nemat and her family and friends, and by extension many fellow citizens are exposed to repression and extremism that will be starkly eye-opening to many Canadian readers. After all that happens to her, including the familial alienation she confronts when she returns from her ordeal, Nemat somehow musters the astonishing and instructive grace to offer a bittersweet meditation on what hatred and outrageously wielded power can do to human decency. A surprisingly redemptive theme and sequence of imagery recurring through the book binds Nemat’s story together, figuratively and literally. It starts in the early pages:It took me five minutes to get to the church. When I put my hand on the heavy wooden main door, a snowflake landed on my nose. Tehran always looked innocently beautiful under the deceiving curves of snow, and although the Islamic regime had banned most beautiful things, it couldn’t stop the snow from falling.

Somehow, the snow is both beautiful, but also unstoppable – delicate, enduring, but sometimes heartbreakingly ephemeral:

One morning in August 1972 when I was seven, I picked up [my mother’s] favourite crystal ashtray. It was almost the size of a dinner plate. She had told me a million times not to touch it, but it was beautiful, and I wanted to run my fingers over its delicate patterns. I could see why she liked it so much. In a way, it looked like a giant snowflake that never melted.

That beautiful object is all too soon shattered, presaging other things that will shatter with the same vulnerability:

His eyes were blank, as he, like me, tried to understand the devastating, lonely gap that death had left behind, the terrible falling from the known into the unknown and the terrifying wait to hit the solid ground and shatter into small, insignificant pieces.

Cumulatively, though, those fragile snowflakes can collect to cool, cleanse, comfort and ultimately offer regeneration, which Nemat clearly and deservedly yearns for after all she has suffered:

It was a perfect summer day, and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky, but I wished for snow to cover the earth; I wished for its cold and honest touch to embrace my warm skin. I wanted my fingers to lose their sense of touch in deep frost and ache. I wanted all the shades of green and red to disappear under the weight of winter and its shades of white so I could dream and tell myself that when spring came, things would be different.

As Nemat simply observes about the place in the world that would finally provide her and her new family with haven and solace: “I liked the name ‘Canada’ – it sounded far away and very cold but peaceful.”

Throughout Prisoner of Tehran, Nemat deals in grief and loss of myriad kinds, in which the destruction of books and writings marches in sorrowful lock step with the death of loved ones. She takes on courageously how one faces different kinds of oblivion, including the shame, silence and denial of friends and family when she re-emerges from imprisonment. That her inspiring tale of singular resilience culminates in her seeking a new life in Canada, where she eventually gets the support she needs to tell this story, is both stirring and gratifying.I love my country already, but Marina Nemat has given me yet another way to articulate what is wonderful about it. Prisoner of Tehran is a strong and deserving choice for all Canadians to read, to appreciate from a startling new perspective just how sweet this country is.

My reviews of other Canada Reads 2012 finalists:

Pingback: A Canada Reads challenge | bookgaga

Pingback: The Tiger, by John Vaillant | bookgaga

Pingback: The Game, by Ken Dryden | bookgaga