Are there names we hold sacred in the CanLit canon, that must always stand alone? With all genuine and due respect, would it be profane to, say, utter anyone’s name in the same breath as the name of Alice Munro … especially if that writer has “punk” and “zine” in his literary curriculum vitae? If it is, what follows is a profane review …

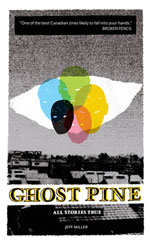

Ghost Pine: All Stories True offers up “all stories true” from the life of author Jeff Miller, covering 13 years from the 1990s to almost the present. The stories are compiled from the best of his long-running zine of the same name. The stories capture Miller’s youth in suburban Ottawa in the late 1990s, to his largely economy class travels across Canada and North America, to his current home in Montreal. Miller’s bleak or just bland urban and suburban settings are gritty and seemingly hard-edged at first, but as the stories progress (and sometimes that progress is charted over mere words, sentences, perhaps a paragraph), most are redeemed by consideration, keen observation, kindness and often inexplicable optimism. What in the world could that possibly have in common with Alice Munro’s oeuvre, where rural and small town settings often belie heartbreak, malice and even menace under a picture postcard, pastoral surface? Both are subversive, in their way, for so clearly undermining what the carefully crafted surfaces – semi-rural southwestern Ontario in Munro’s case, downtown or suburban Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Winnipeg, Edmonton et al in Miller’s case – would seem to depict. Both imbue their settings and characters with quiet, almost mundane solidity, but, *because* they’re quiet, modest and mundane, are therefore profoundly authentic situations and people with which we can relate. Miller’s bike couriers, security guards, struggling musicians and artists, mildly and sheepishly disaffected high school students, not to mention the person and persona of Miller himself (because all of his stories are true, remember) might seem depressed, unmotivated, ready to wreak havoc or to just give up. But they all keep going in one fashion or another and they all strive to learn and expand their horizons beyond their immediate circumstances and experiences, best illustrated by the centrepiece set of stories and fragments about “The Social Justice Club”, where a loosely assembled group of misfits strives to find a cause or purpose beyond their day-to-day high school routines. Just as it is charmingly surprising to see these teenagers struggling to understand the issues associated with East Timor or Burma, or the value of becoming a vegetarian, it is almost startling and simultaneously heartwarming to observe a young person ungrudgingly helping his wheelchair-bound grandfather to the bathroom, and then listening not only patiently but with fresh appreciation to an oft-told reminiscence.“I laughed, not with the childish glee I did the first time I heard the story many years before. But today it was actually kind of funny.

My grandfather wiped a tear of joy from his eye.”

The all true Ghost Pine stories have the intimacy of a handwritten, manually cut and pasted, collated and assembled publication – as they should. That homemade aesthetic does not, however, suggest that there is any compromise in sophistication in the storytelling. That’s again where I think the Alice Munro comparison is sound. Miller’s Ghost Pine stories have the same finely honed care and craft as Munro’s plainspoken words of bottomless depth and possibility. Both speak simply and resonantly of familiar people, locales and experiences, even though they are widely divergent on the surface.

Thank you to Invisible Publishing for providing a review copy of Ghost Pine, by Jeff Miller.