Guest contributor Liza Achilles

I keep hearing the same lament, over and over.

I host a Silent Book Club, which means that I meet weekly with people who love to read. We talk about the books we are reading … and not reading, as the case may be.

During club meetings, I keep hearing people bemoan their lack of concentration. Everyone’s brain is going haywire. Everyone’s worried about COVID-19. Everyone’s worried about politics. Everyone’s stressed about social distancing and the shuttering of schools and workplaces. On top of all this, everyone’s being bombarded with phone notifications, social media messages, and news alerts.

It’s not surprising that sitting down and calmly reading a book is starting to seem like a quaint luxury, something that old-fashioned people did in previous centuries.

But reading full books — and not just snippets of news or gossip — brings massive rewards. Many of us want to read more books. We just need to figure out how to hack our personal systems, how to reconfigure our brains, to allow it to happen. Following are solutions that work for me.

How to Have a Shot at Reaching Your Reading Goals

You aren’t going to reach your reading goals if you don’t have any in the first place! So that’s a good place to start.

All of the most avid readers I know track their reading. Some people track their reading on Goodreads. Other people use digital spreadsheets. I, personally, am analog: I use a notepad in which I write down, by hand, the date I finished a book and its title and author. Simple.

Tracking your reading is great for motivation. You can learn how many books you typically read in a month or a year. And you can set goals to increase those numbers. On days when you don’t feel like reading, you can think about your goals, which may prompt you to sit down with a book.

A friend of mine doesn’t track number of books read per year, but rather number of pages read per year. She uses the page count supplied by her e-reader, so it’s a consistent measure. This, she feels, and I’m sure she’s right, is a more accurate gauge of how much she is reading.

I like to have daily page count goals in addition to my monthly and yearly goals. I try to read at least 40 pages a day. This doesn’t always happen, but having the goal helps.

How to Start Reading

There are always a hundred things I could be doing. Dishes, laundry, cooking, cleaning, exercising, texting, going on social media … the list goes on and on. I have noticed that there are points in my day when I think, “I should read a book,” but instead I end up clicking on each of my phone apps, in turn, to see what’s new there.

I have discovered that, nowadays, I need a motivator to inspire me to sit down with a book. Once I start reading, I’m often swept away by the joy of reading. But I need something to get me there in the first place.

For me, the best incentive is something to put in my mouth. (I’m like a baby!) My beverage of choice is tea, either caffeinated or herbal, depending on the time of day. My food of choice is a piece of hard candy.

I say to myself, “If you sit down to read, you can have this savory drink or sweet candy!” I don’t allow myself to eat an entire jar of candy, mind you — only one or two pieces per day. It’s just a brain boost to get me started.

Once I get started, I often forget about the tea or candy as I get engrossed in the book. Sometimes I look up an hour later and notice a full mug of cold tea, tea bag still dangling over the edge—how silly is that?!

How to Keep Reading

While reading, I often feel the urge to check my phone. I have tried turning it off or putting it in another room; but inevitably, I will need it, wanting to look up a word or a reference in the book I’m reading.

Instead of banishing my phone from my presence, I tell myself, “This is your reading time. Try not to check your phone. But if it rings or beeps, or if you can’t resist and pick it up to check it, put it down as soon as possible.”

Sometimes I give myself permission to click around on my phone only after I have read a certain number of pages, or gotten to the end of a chapter.

Also: I silence almost all notifications on my phone. There are literally only three types of functionalities or people that I allow to make a noise that might disturb me. Some people might say even three is too many. You might try putting your phone in Total Silence / Do Not Disturb mode if being interrupted while reading is a problem.

How to Combat Reading Fatigue

I find that it’s helpful to space reading throughout the day. Read a few pages in the morning, a few pages at lunchtime, and a few pages before bed.

Making it through a massive chunk of reading all in one sitting can work if the book is a real page-turner. But there are lots of great books out there that need to be digested, so to speak. Spacing out the book’s consumption helps your brain process what was read and recoup before the next session.

Additionally, one of my favorite times to read is in the middle of the night. Sometimes I wake up late at night and read for an hour. It’s a time of day when I don’t feel at all distracted. There’s no breaking news; little is happening on social media; all my friends are asleep. I always get a lot of reading done when I read at 1 in the morning. Waking early and reading at 5am is also productive for me.

How to Get Through Reading Slumps

Sometimes it’s hard to get reading done because you just finished a good book, and no other book seems interesting.

Or maybe you are in a slump because you tried reading one book, but it was boring, so you picked up a second book, but it was boring, too, and you feel guilty about not reading either of them, and you wonder whether you should try a third book, or plug away at one of the other two, and you can’t make a decision, so you give up and take a nap.

In my experience, the best remedy for this problem is to have lots of books at hand. Always have at least 20 unread books lying around. These can be books you own or books from the library, real books or e-books.

Book reading is extremely personal and circumstantial. If you don’t feel like reading a particular book, it could be simply the wrong book for you, at this point in your life. I recently tried to read a book multiple times, but failed each time … until the political climate changed. Suddenly, I was able to read about that topic again. Before that, the topic felt too painful and raw. Afterward, I devoured the book.

However, in the thick of things, I did not realize that that was the problem. I just thought I was having a problem with reading in general. In reality, I was having a problem with a particular emotional trigger.

The lesson is, have a bunch of books around, and keep trying to read one, and then another one, and then another one, until you find one that resonates with you, right now. That’s the book that you should be reading.

And I wish you the best of luck in reading it!

Liza Achilles is a writer, editor, poet, and coach based in the Washington, D.C., area. She blogs about seeking wisdom through books and elsewhere at lizaachilles.com.

It was such an honour to collaborate with Liza, developing reciprocal pieces on the challenges of reading during these unsettled and unsettling times. It was fun, too! We wrote our pieces independently, exchanged them and then opened and read each other’s pieces at the same time. It was thrilling to see how what we observed and how we were dealing with it had common threads and complementary strategies, creating a really interesting balance that we hope all our bookish friends will appreciate. Liza beautifully presents my piece on her blog here: Clutching Our Books While Riding a Rollercoaster: the Solace and Challenges of Reading During a Pandemic.

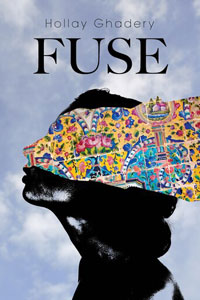

Fuse, by Hollay Ghadery, is a remarkable book. I’ve seen it labeled “memoir,” but I’d describe it as a collection of personal — very personal — essays. Organized around themes, the chapters include poetic fragments and reflections, narratives and insights, considerations and re-considerations. Instead of building to a narrative climax, this rich material forms a mosaic, a representation of a life that’s coherent but still in progress. Ghadery deftly supplements her lived experience with background information to give readers insight into a larger cultural context.

Fuse, by Hollay Ghadery, is a remarkable book. I’ve seen it labeled “memoir,” but I’d describe it as a collection of personal — very personal — essays. Organized around themes, the chapters include poetic fragments and reflections, narratives and insights, considerations and re-considerations. Instead of building to a narrative climax, this rich material forms a mosaic, a representation of a life that’s coherent but still in progress. Ghadery deftly supplements her lived experience with background information to give readers insight into a larger cultural context.